View this page at 1024x768 This page last updated Jan 2008. Thanks to the efforts of the people who browsed old newspapers of the time, a comprehensive searchable database of old boat information exists online at the Moray Council LIBINDX page. This lists some 120 Zulus launched by McIntosh's in 20yrs from 1883 to 1904. Please contact me for comment or if you can help with extra information.

Find out more about

And also the Mesothelioma Fund

|

The first Zulus were clinker built (as were the Scaffies), a construction method which limited their size to a keel length of around 40ft. The first recorded McIntosh built Zulu was the BF 893 McIntoshes launched for Alex. McIntosh in 1883. In the mid 1880's the carvel method of construction was adopted for the Zulu, which allowed the building of the larger vessels being required by the fishermen. As can be seen from this 1888 newspaper article, the McIntosh's apparently quickly adopted & mastered this new technique. |

|

Fishing & General Gazette 19th April 1888 BOAT LAUNCH

|

|

|

These two Zulus, the BF 333 Helen & Margaret & the BF 339 Fame are reported as having been 'fitted up with the latest improvements, including capstans which are gradually coming into use on board fishing boats.'

It is unclear if the capstan referred to is a steam capstan or a hand operated capstan as seen in the photo by ally. The steam capstan was invented by a Mr.William Elliot of the firm Elliot & Garrood, and the first one was fitted to a fishing boat at Lowestoft in 1884. This Beccles steam capstan not only assisted in the hauling of the nets, but provided the extra power needed to sheet home the larger sails required to power the ever increasing size of the Zulus. This size increased gradually from the 65 footers described here in 1888, to the 80ft plus examples built in the early 1900's, such as SY 486 Muirneag which became perhaps the most famous of all Zulu, fished continuously by her owner Alexander 'Sandy' MacLeod from 1903 until 1939, earning the reputation as probably the last British herring drifter to fish under sail power alone. The last recorded Zulu launched by the McIntosh's was the BF 1488 Loyal launched in April 1904. Thanks to information received from the Buckie & District Fishing Heritage Centre, the last Zulu built by the McIntosh family was M SLATER BCK57 launched in Jan 1910 from the Ianstown yard. |

|

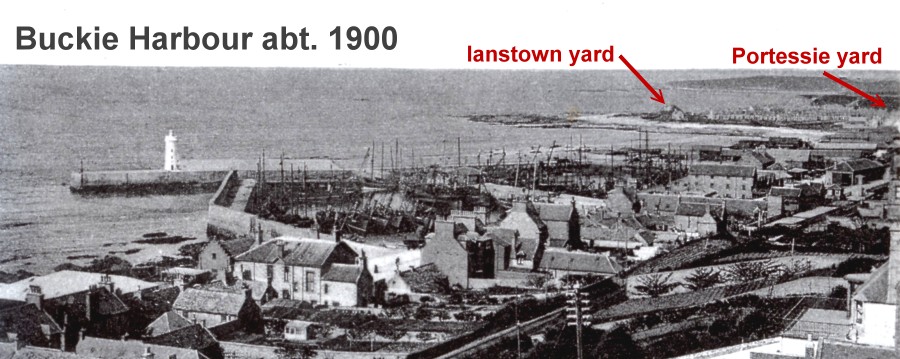

All the McIntosh built Zulus were constructed under cover in either the shed at Peterhythe, Portessie, or the shed on the point at Ianstown. The early boats (1888) were around 65ft o'all, increasing steadily to the 80ft o'all models, as the last were built in 1903 - 1904. (The Steam Drifters were built in the open on the beach).

|

After the completed hull was launched (in favourable weather conditions) from the temporary slipway, it was then presumably taken in tow to the nearby Cluny Harbour for fitout. Masts had to be fitted - obviously requiring the use of some form of crane. The vertical boiler & steam capstan had to be installed. Yards & sails had to be brought aboard to make her seaworthy as well as the nets & other fishing gear to complete her transformation into a herring drifter. |

|

During the transition from the Scaffie, the sail configuration of the Zulu changed little, the main difference being the increase of their size. They were still made of cotton canvas and required periodic dressing (tanning) with cutch to help preserve them. (Synthetic material was not invented until the 1950's).

|

|

Though mostly used for drift net fishing for herring, most Zulus were also used for great & small line fishing as were the Scaffies. (Small line fishing meaning a boat worked close inshore, & great line fishing meaning they travelled further afield to deeper water). The introduction of the steam powered capstan onto the Zulu in the mid 1880's made the job of hauling in the nets much easier. Other than this the method of fishing remained largely unchanged from the era of the Scaffie, as indeed it remained unchanged through the era of the Steam Drifter. 'An experienced eye can judge from the colour of the water if the shoals are about - -' |

|

Although far less complex than the Steam Drifter, there was still much work to be done ashore to hopefully ensure the Zulu a successful fishing trip.

|

|

|

'Sailing Drifters'

After reaching the fishing grounds, the skipper then decided where to cast out his nets. There would have been considerations such as proximity to other boats & the look of the water. 'Their whereabouts is indicated by various signs - the slight trace of oil on the surface from the glands exuding the lubricating mucus which reduces the friction between fish and water - the presence of abnormal numbers of seabirds, grampus, or cod near the surface.' Sails were then lowered & the Zulu allowed to drift while the nets were payed out on the starboard side. Little changed from the method on the Scaffie page. The use of animal skin buoys was replaced by cotton canvas as were probably these shown on the 'Annie Jane'. |

|

The First World War saw a rapid acceleration in technology & the development of smaller more powerful oil engines, meant the fishermen had another much less expensive option than the steam drifter. This option was to have motors fitted to their sailboats. From around 1917 some McIntosh built Zulus were converted. The BF 1042 Bonnie Lass, built 1898, was fitted in 1917 with twin 26in stroke Kelvin engines. The BF 736 Craigview, built 1902, was also fitted with twin Kelvin engines in 1917. BF 954 Strathlene, also built 1902, was fitted with a 75hp Gardner engine in 1918. Yet another brand of engine was fitted to BF 1471 Mayflower, built 1904, when two 45/50 Gleniffer engines were installed in 1918.

Photos by ally of Findochty, of the McIntosh built zulu BF 1091 PASS AWAY launched 1903 for Sutherlands of Findochty. She was fitted with an engine (date unknown). Renamed Laurel (date unknown) and was still fishing in the 1950's.

|

BCK 314 Thistle |

|

Mr. Ron Stewart "Sail & Steam" Moray District Library Buckie District Fishing Heritage Museum Banffshire Advertiser 'Sailing Drifters' Edgar March Gordon Williams - Professional model builder Robert Dennis - Professional artist David Williamson David Mair McIntosh family history sources |