View this page at 1024x768 This page last updated Jun 2017.

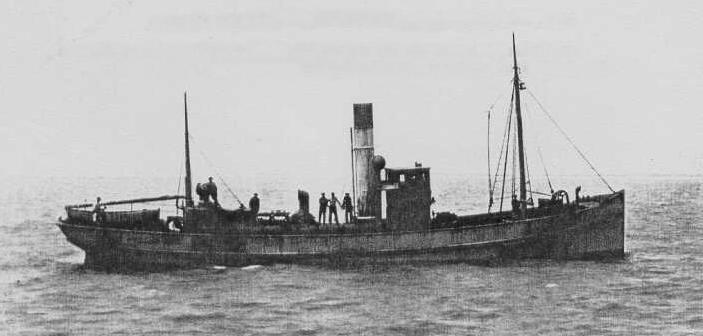

This webpage came about as a result of my family history research involving the sailing vessel 'Sound of Jura'. I was given a document (Thanks to Margaret Cox from Melbourne) detailing the life of Carl Ossian Johnson, written by his daughter Esther Oceana Greenwood. I thought it historically important, and hopefully of interest to many researchers.

This proved correct and further information and photos came to light thanks to his grandaughter Micaela Schoop from England and Margareta Bjorck from Sweden (who was related to his first wife Stina).

Please contact me for comment or if you can help with extra information. |

1867 - 1949

A Swedish pioneer in the South African fishing and whaling industry. As recorded by his daughter, Esther Oceana Greenwood (nee Johnson), with further information and photos from his grandaughter Micaela Schoop and a relative of his first wife Stina, Margareta Bjorck.

|

|

|

From Margareta Bjorck from Sweden (The original correspondence from Margareta Bjorck in Feb 2011 can be read at the bottom of the page)

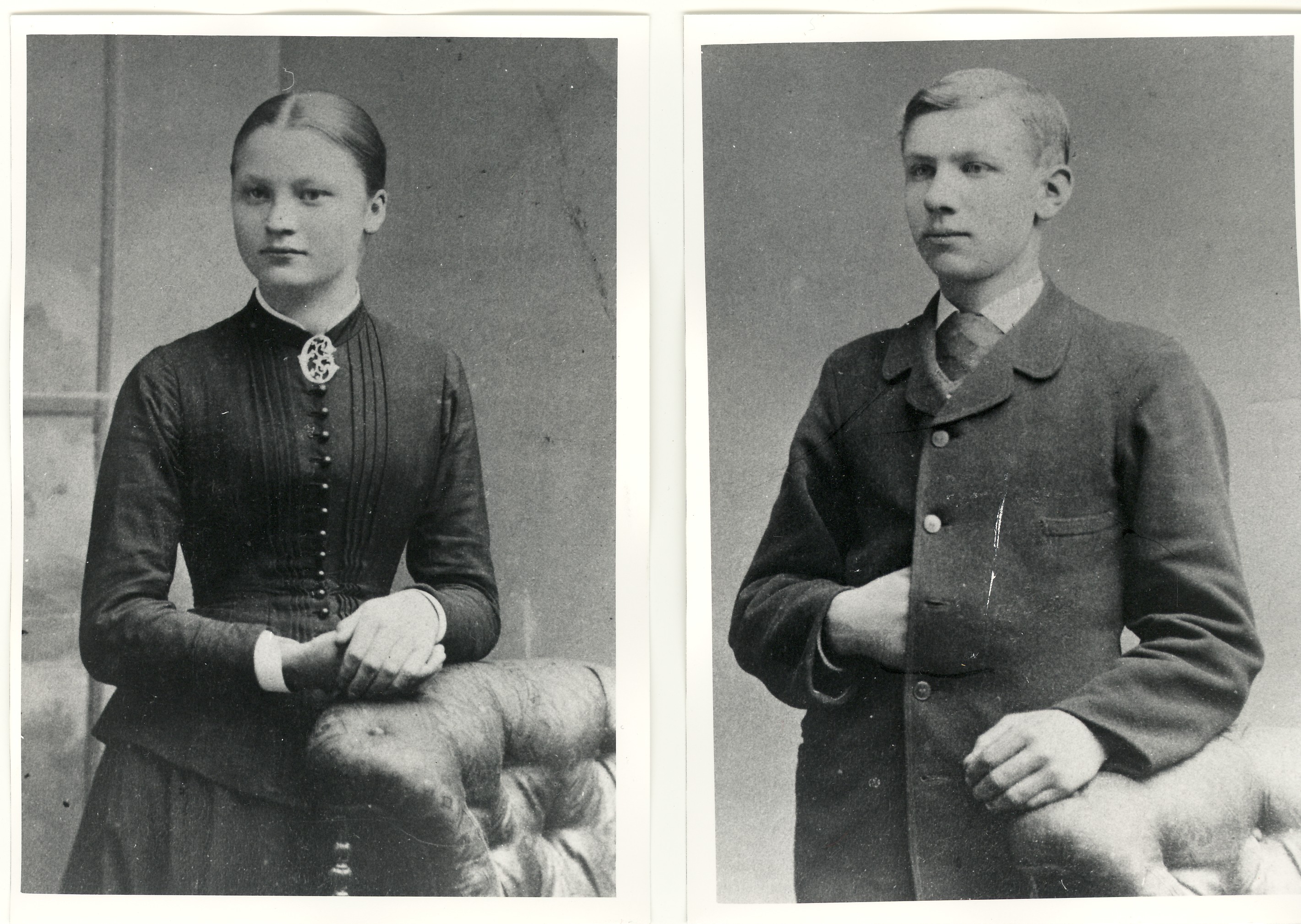

I'm a Swede, dealing with geneological research, and I have read the story about Carl Ossian Johnsson with great interest. I'm not related to him, but to his first wife Christina (Stina), who was a cousin of my grand-father. Thanks to this website I found Micaela Schoop, descendant of Carl Ossian and Esther. We have also got in touch with relatives of Siri. Together we have combined our pieces of the puzzle of the private life of Carl Ossian Johnson to new conclusions. Most fruitful was that we succeeded to determine the dates of the divorce court cases between Carl and Stina, which gave us access to the very extensive court documents. Obviously none of Carls women nor children knew the full truth about his different relations, and even if we know more today than each one of them did, there might be more secrets left to reveal. From what we know now, I try to make some additions (in text and photos) to the story written by his daughter Esther Oceana: In the album of Stina's aunt, we have found these two photos of Stina and Carl in their teens, about 1885-87, when their childhood friendship had turned into some kind of love story.

From New York Carl wrote a letter to Stina in Vaxjo, and asked her to come to him in New York. Stina arrived in November 1891 and they married the 8th of June 1892. Stina worked as a cook and Carl got a temporary job at a shipyard a few days a week, and we have heard that he also now and then worked on ships.

This is probably a wedding photo of Calle & Stina

The 6th of September 1893 Stina and Calle got twin boys in New York. Their names were Callie and Eric, so then Carl had two sons named Erik/Eric! The family had problems to support themselves in NY and the twins were small and weak. In 1894 they all went to Sweden (Stina and the twins on paid tickets, Carl by working on a ship), to see if life would be better there, but they decided to return to NY. On their journey back on the ship Lucania in November 1894, the ship got into a terrible storm, that lasted for two days. The son Eric died on the ship the 20th of November.

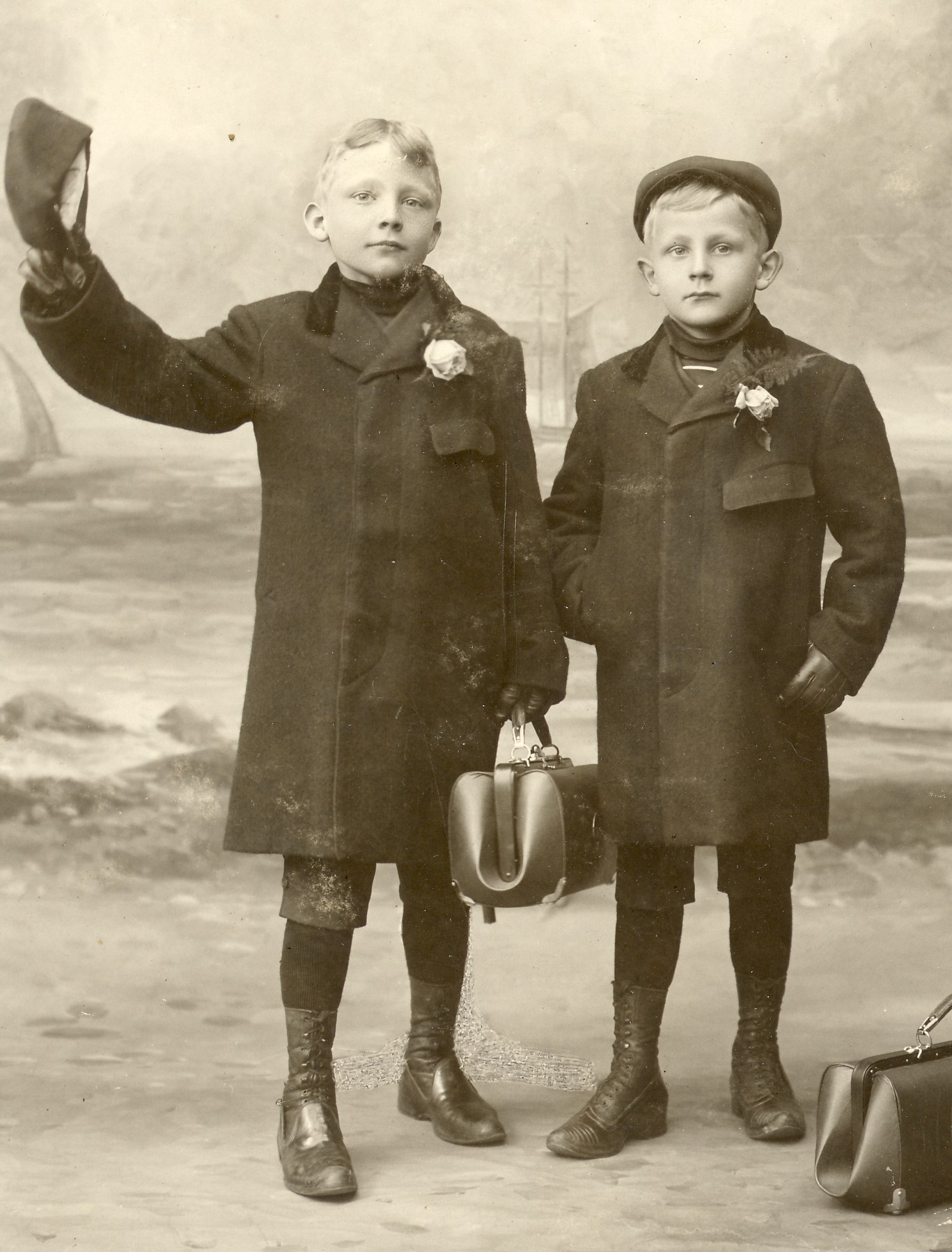

Stina with twins Callie & Eric In 1902 the whole family again went to Sweden, to see if it would be possible to live there. This time it was not because of poverty. They had money to buy tickets for the whole family, and for living during a long stay abroad and were able to employ Stina's sister and Carl's brother to run the business in Durban during their absence. Maybe they were longing for family and friends, maybe they found it better for the boys to grow up in Sweden. But as a result of their more than a year long stay in Sweden, Carl decided to buy a trawler to start fishing in South Africa. For three months the whole family stayed with the shipbuilder and his family. Stina noticed Carl's eyes on the shipbuilder's 16 years old daughter - Esther - but Carl promised his wife to give up any thoughts of the young girl. Carl and Stina decided that their sons, 7 and 9 1/2 years old, should not follow them back to South Africa on the newly-built trawler. Instead in spring 1903 they were sent (alone) from Sweden to a boarding school in the USA.

Callie & Sigurd The success of the trawler 'Berea' made Carl in 1906 order one more trawler from Sweden. When he was in Gothenburg he again met Esther. The 22th of January 1907 Esther's mother died, the 4th of February Esther became 21 years old and empowered to run her own business. The 6th of February she obtained a moving certificate for emigration to South Africa. At about the same time Carl's oldest son, Erik from Gothenburg, almost 16 years old, arrived in Durban and got a job on his father's ship 'Germania'. The 30th of May Carl wrote to Stina that Esther has followed him to South Africa, and that he wants to divorce. In 1909 Carl made a will saying that after his death Stina should get 50%, Esther 25% and Lilly and Erik 12.5% each, and he makes Stina and Esther joint executors. Stina knew about Esther and the daughter, but she still didn't know about Carl's first two children nor about her husband's testament. When Esther in 1909 returned to Sweden with her daughter, Stina believed that the affair between her and Carl was over. Esther, on her part, believed that Carl had separated from Stina (and as we see in the story written by Esther Oceana, she believed that the separation between Carl and Stina took place long before he met her mother.) In reality it seems as Carl combined living with Stina, Esther and - from 1913 - also Siri. According to what was presented in the court, there were no efforts from him at this time (1909-1916) to obtain a divorce. Probably he gave priority to his business life. Or he had no problems with the present situation.

Stina with Callie & Sigurd Probably taken in 1917 before the boys went to WW1 In 1916 Carl formally recognised Esther Oceana as his daughter and from that year he also tried to persuade Stina to initiate a divorce process in South Africa. The law in SA gave the power to initiate a divorce only to the person that has been abondoned, so he couldn't do it himself. In Sweden the laws were more favourable to him, but he didn't want to lose his British citizenship. However he never succeeded in making Stina take such an initiative. In 1925 he started the first court case between himself and Stina, in a little countryside court in Sweden, close to Carl's summercottage, that he at that time had registered as his permanent dwelling, combined with a regaining of a Swedish citizenship. As far as we have seen, Stina won the important parts of the processes. She obtained a separation of property and got lots of money, but Carl didn't get any divorce. The Swedish court stated that as Carl lived in Sweden and Stina in South Africa, the terms in the laws of both the countries for getting a divorce must be met. The terms in the Swedish law were met, but the terms in the South African law weren't. Therefore Carl in 1933 got the idea to request a divorce in Riga, Latvia, where the laws admitted even foreigners to get a divorce based upon their liberal law. We haven't found the date of divorce. But we know that he (after having asked Esther, who declined) married Siri in Riga the 9th of February 1934.

Siri Carl and Sofia's daughter Lilly stayed in western Sweden and kept in touch with her father. We have heard that he financed the house where Lilly and her husband lived in Trollhattan, which is just half way between Vaxjo and the harbour Sandefjord in Norway, where Carl's whaling boats often were in summer, to exchange crews. So Carl and his companions now and then stayed overnight with his daughter when they drove from Vaxjo to Sandefjord. But his other daughter, Esther Oceana, obviously never knew about her 21 years older half-sister. What about Carl's degrees from navigation school? Esther Oceana writes that her father always told her and her mother that he had passed out from the Navigation School in Gothenburg, but that she had checked their alphabetical register of students and his name did not appear. In the court Carl presented a document saying that he passed out in Malmo 1890, as a mate the 30th of April and as a captain the 14th of June. Beside that this seems to be a very quick advancement from mate to captain, Carl's first two children were born in Gothenburg 1889 and 1891 - 276 kilometers from Malmo, which was quite a distance in those days. There are even other facts, that make me doubt: If he had a degree from a navigation school, why did he have those big problems to support himself and his family in New York? Why did he start a rickshaw business and sell bikes in Durban? And if he had a captain's uniform ? why didn't he wear it in any photo, for instance at his wedding? One explaination could be that he took private lessons from an elderly captain and/or bought false documents. But we don't know.

|

|

My sincere thanks are due to Mr. Lawrence Leask, director and employee of Irvin & Johnson Limited for fifty years for allowing me access to a confidential file entitled 'The History of Irvin and Johnson Limited' ; Part I from 1903 - 1922 is type-written, Part II is hand-drafted with some pages missing and was never completed. The author of this document is Mr. H. Abao, one time secretary and Director of Irvin and Johnson Limited. I am grateful to Mr. Greener, secretary of Irvin and Johnson Limited, for letting me study a history of the firm compiled by Mr. Eric Rosenthal. Ione and Jalmar Radner helped me to edit the story. And last, but not least, I wish to thank Irvin and Johnson Limited for their kind assistance in having the manuscript typed. |

|